Rubber is known around the world for one thing, tires. While tires still account for over 60% of worldwide rubber use, it is used in everyday products from tennis shoes to the erasers on the common pencil. OEM’s, automotive and medical manufacturers alike value rubber for its elasticity, flexibility, low gas permeability, water repellency, electrical insulation and chemical and abrasive resistance. Advances in deflashing, ultrasonic cleaning and other mass finishing techniques have opened new areas of application for these unique polymers.

Rubber is known around the world for one thing, tires. While tires still account for over 60% of worldwide rubber use, it is used in everyday products from tennis shoes to the erasers on the common pencil. OEM’s, automotive and medical manufacturers alike value rubber for its elasticity, flexibility, low gas permeability, water repellency, electrical insulation and chemical and abrasive resistance. Advances in deflashing, ultrasonic cleaning and other mass finishing techniques have opened new areas of application for these unique polymers.

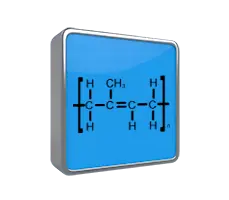

All rubbers are polymers with a high molecular weight consisting of long, loosely woven, repeating, chains of molecules. This structure enables rubber to be stretched under stress and then return to its previous form without permanent deformation.

Rubbers are broadly categorized into natural rubbers, those originating from Pará or other similar rubber trees, and synthetic rubbers, those derived through the polymerization of petroleum based monomers. Both forms share many of the same mechanical properties, but synthetics have a much greater thermal stability and are more compatible with petroleum products. Roughly two-thirds of all rubber produced globally is synthetic and its share of the market is expected to rise.

The Olmecs began working with natural rubber as early as 1600 BC and soon thereafter passed on their knowledge to the Mayans and Aztecs. Columbus and other explorers brought samples of the new product to Europe where scientists continued experiments through much of the 1800’s. In 1839, the pioneering work of Charles Goodyear and his discovery of vulcanization, the process of using heat and pressure to make rubber harder and more durable, changed the role of rubber forever. With skyrocketing values and shortages of natural rubber, scientists like Bouchardat and Lebedev, realized the potential of developing synthetic rubbers. Work continued at a fevered pitch in the early 1900’s and with Americas entry into WWII the U.S. military was producing synthetic rubber at a level more than twice the entire worlds pre-war natural rubber production.

Today’s rubber products are integral components to all manufacturing industries including the automotive, aerospace, dental and medical fields. In the rubber molding process, rubber polymers can be forced through small holes under high pressure to create long strands. Injection molding, introducing a heated polymer mixture into a mold chamber and vulcanizing it with steam, is one of the most widely used fabrication methods for rubber molding. Combining rubber strips into a mold under intense pressure and heat in the compression molding process is another widely used manufacturing technique. As with any other item created through rubber molding, rubber products still require some degree of surface finishing before they are ready for integration into the finished product.

ISO Finishing has worked with OEM’s, medical device manufacturers and injection molding companies to custom tailor isotropic finishing processes for each specific product. Whether tumble polishing o-rings for hydraulic industry or centrifugal barrel finishing seals for dosing pumps for a medical device manufacturer, we have the deflashing, polishing and cleaning expertise for each unique application. Send us a batch of sample parts and we will provide several documented examples of different surface finishes for you to choose the one best tailored to your application.